Giants used to roam over every single corner of the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. Elephas

maximus sumatranus—Sumatran elephants—lived among the island’s thick and towering

jungle. Until 40 years ago, there were still almost five thousand individuals of them.

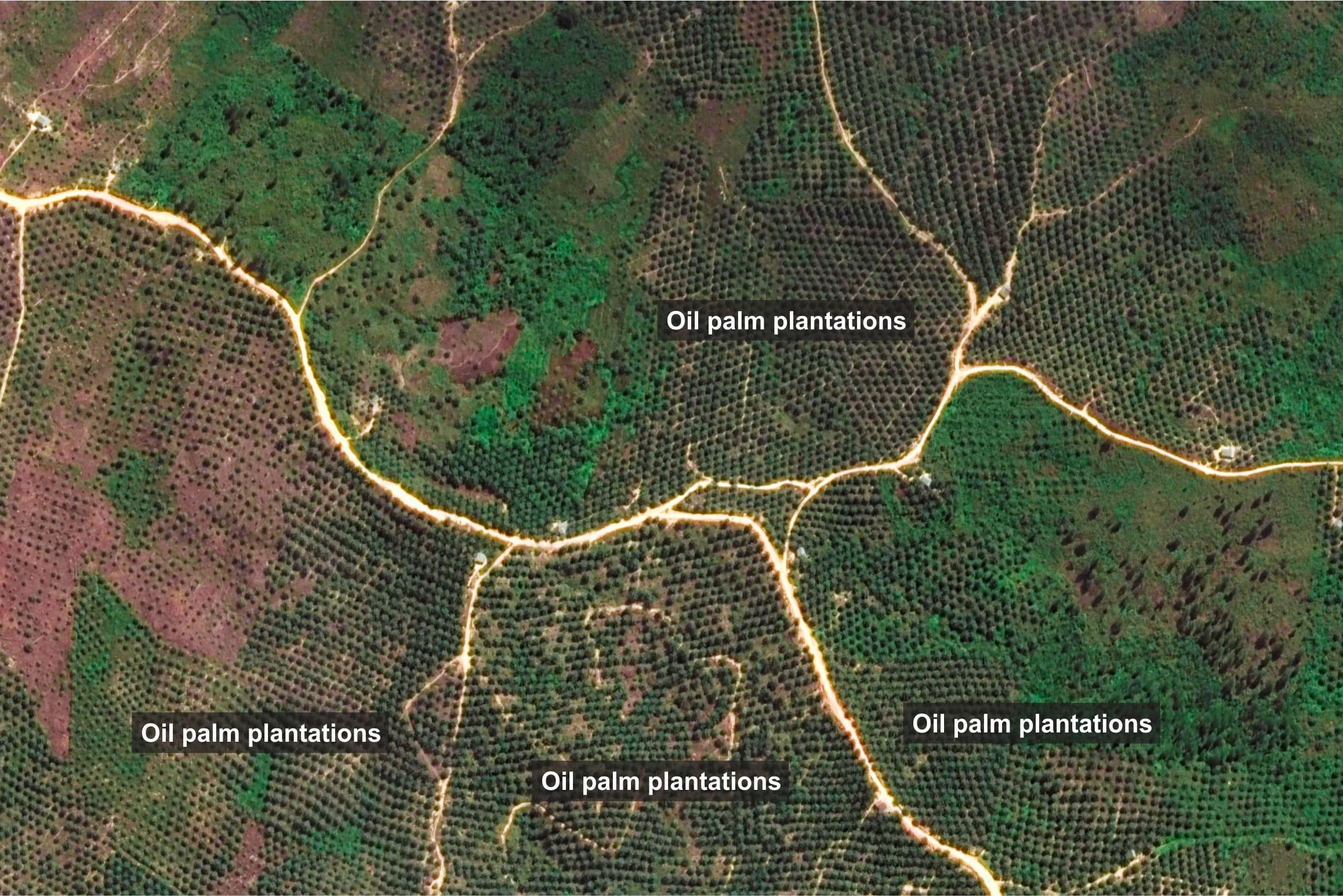

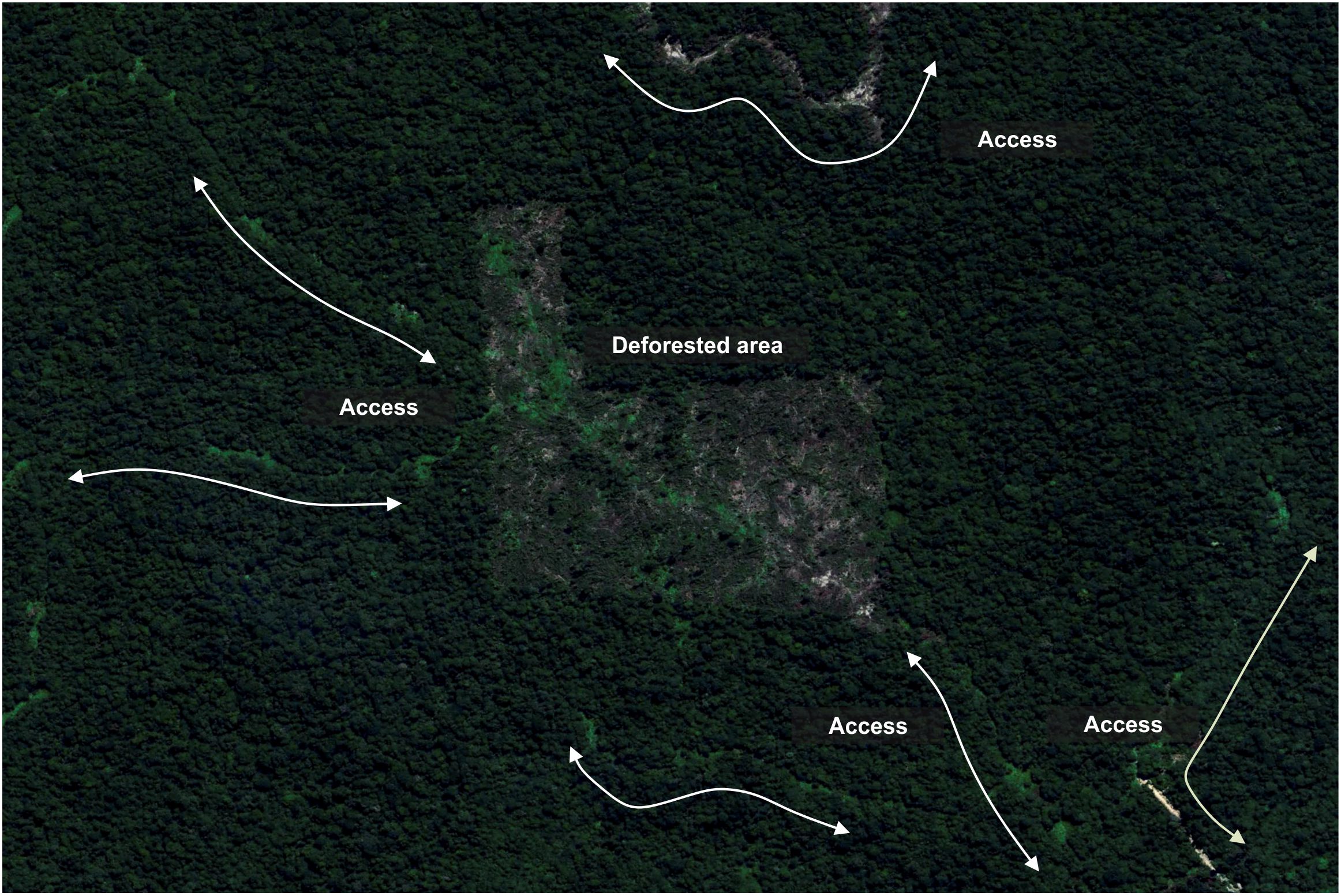

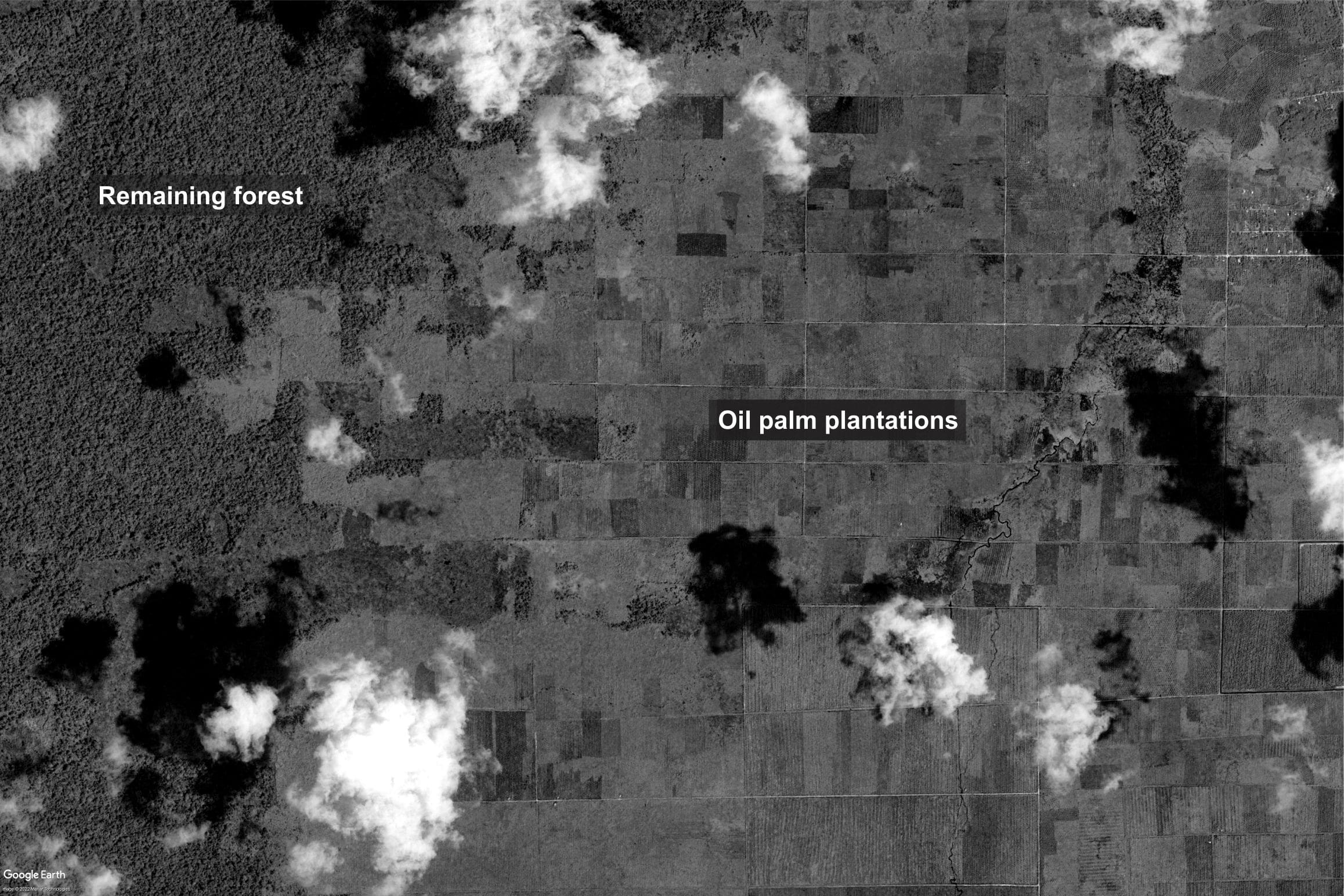

But as plantations and industrial forest areas annexed the jungle, the elephants diminished. In

2017, the estimation plummeted to only less than two thousand individuals[1]. They even have

been extirpated in numerous areas, namely West Sumatra Province[2]. Today, the population is

still counting down.

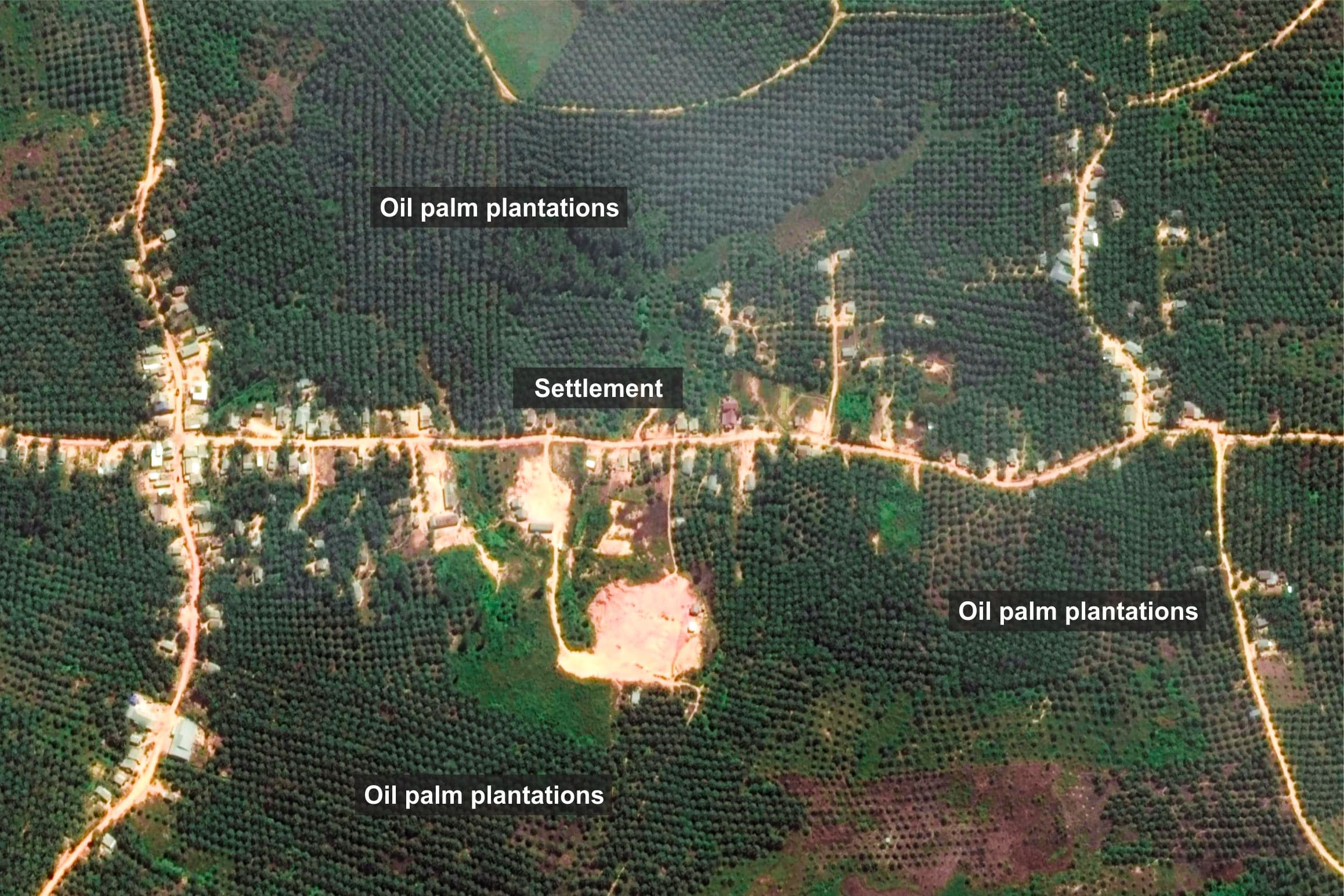

Those remaining elephants are jammed into a more and more fragmented and shrinking habitat.

Because of this, many packs are forced to wander near human settlements and plantations where

conflicts become inevitable.

Weight: 3 - 5 tons

Maximum height: 3.2 meters